Don't Scapegoat President Obama For Sick, Addictive Economy

This document was uploaded by user and they confirmed that they have the permission to share it. If you are author or own the copyright of this book, please report to us by using this DMCA report form. Report DMCA

Overview

Download & View Don't Scapegoat President Obama For Sick, Addictive Economy as PDF for free.

More details

- Words: 2,295

- Pages: 9

Don’t Scapegoat President Obama for the Failure of Our Sick, Addictive, Economy By Jed Diamond, Ph.D. Contact: [email protected]

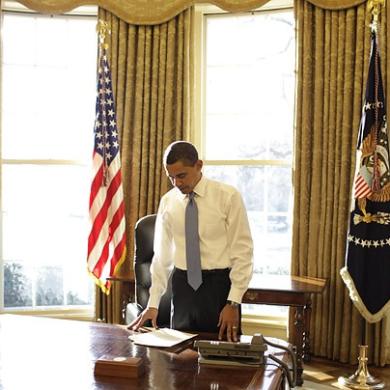

Let’s face it, no matter what the latest ups and downs we read in the news, the economy is still sick. And predictably President Obama’s approval ratings are dropping. When he was elected most of the world felt hopeful that Mr. Obama could make a difference and turn things around within the country and with our relationships around the world. Democrats were looking forward to major changes in health reform and an end to the dysfunctional economic policies of the Bush years. Republicans were worried that Obama would change America in a way not to their liking. All felt he was destined to have a major impact on our lives. I think he has and he will. It’s great to have a man who is charismatic, intelligent, thoughtful, willing to work with disparate groups, and a man who seeks reconciliation rather than conflict. But I’m afraid the nature of the problems we face are not going to be solved by even the most intelligent, hard-working, and dedicated President. If we

recognize that we can hope for the best, but be prepared for the worst, and resist the temptation to make the President the scapegoat for our unfilled expectations, we will be able to take responsibility for creating the kind of country and world we truly want and need. For those a bit rusty on their biblical history, in Leviticus, the scapegoat is loaded own with the sins to which the ancient Israelites have confessed and then banished into the wilderness. The word "scapegoat" has come to mean a person, often innocent, who is blamed and punished for the sins, crimes, or sufferings of others, generally as a way of distracting attention from the real causes. Most of us have been “scapegoated” in our lives and it’s not very comfortable. It order to prevent this from happening to President Obama (or anyone else) we have to get a clearer picture of the nature of our economic ills and what the true causes of failure might be. So why are both the U.S. economy and the larger global economy ailing? Those in positions of power, i.e. the mainstream media, world leaders, and America’s chief economists, Treasury Secretary Geithner and Feberal Reserve Chairman Bernanke) offer near unanimity in their opinion: Those recent troubles are temporary and are primarily due to a combination of bad real estate loans and poor regulation of financial derivatives. As a health-care practitioner, I know how important it is to have the correct diagnosis of an illness if treatment is to be most effective. If this conventional diagnosis is correct, then the treatment of our economic malady might logically include heavy doses of bailout money for beleaguered financial institutions, mortgage lenders, and car companies. Plus

better regulation of derivatives and futures markets. And finally, stimulus programs to jumpstart consumer spending. But Richard Heinberg, a fellow at the Post Carbon Institute, and a man I have learned to respect greatly over the years (not the least because he usually turns out to be right), has a different take on what ails us. “I am suggesting an Alternative Diagnosis,” says Heinberg. “This explanation for the economic crisis is not for the faint of heart because, if correct, it implies that the patient is far sicker than even the most pessimistic economists are telling us. But if it is correct, then by ignoring it we risk even greater peril.” When James Howard Kunstler wrote The Long Emergency in 2005, he said that the greatest danger this society faced would be its inclination to gear up a campaign to sustain the unsustainable at all costs -- rather than face the need to make new arrangements for daily life. This seems to be what is happening at the top levels of power. Peak Oil and the Limits of Growth For several years, a swelling subculture of commentators (which includes Heinberg, Matt Savinar, Carolyn Baker, James Howard Kunstler, and others) have been forecasting a financial crash, basing this prognosis on the assessment that global oil production was about to peak. As summarized by Heinberg in his August, 2009 Museletter (www.RichardHeinberg.com), their reasoning went like this: Continual increases in population and consumption cannot continue forever on a finite planet. This is an axiomatic observation with which everyone familiar with the

mathematics of compounded arithmetic growth must agree, even if they hedge their agreement with vague references to "substitutability" and "demographic transitions." Energy is the ultimate enabler of growth (again, this is axiomatic: physics and biology both tell us that without energy nothing happens). Industrial expansion throughout the past two centuries has in every instance been based on increased energy consumption. More specifically, industrialism has been inextricably tied to the availability and consumption of cheap energy from coal and oil (and more recently, natural gas). However, fossil fuels are by their very nature depleting, non-renewable resources. Therefore (according to the Peak Oil thesis), the eventual inability to continue increasing supplies of cheap fossil energy will likely lead to a cessation of economic growth in general, unless alternative energy sources and efficiency of energy use can be deployed rapidly and to a sufficient degree. Of the three conventional fossil fuels, oil is arguably the most economically vital, since it supplies 95 percent of all transport energy. Further, petroleum is the fuel with which we are likely to encounter supply problems soonest, because global petroleum discoveries have been declining for decades, and most oil producing countries are already seeing production declines. So, by this logic, the end of economic growth (as conventionally defined) is inevitable, and Peak Oil is the likely trigger. Increased Growth Leads to Increased Debt Which Can No Longer Be Serviced Why would Peak Oil lead not just to problems for the transport industry, but a more general economic and financial crisis? During the past century growth has become institutionalized in the very sinews of our economic system. Every city and business wants to grow. This is understandable merely in terms of human nature: nearly everyone

wants a competitive advantage over someone else, and growth provides the opportunity to achieve it. But there is also a financial survival motive at work: without growth, businesses and governments are unable to service their debt. And debt has become endemic to the industrial system. During the past couple of decades, the financial services industry has grown faster than any other sector of the American economy, even outpacing the rise in health care expenditures, accounting for a third of all growth in the U.S. economy. From 1990 to the present, the ratio of debt-to-GDP expanded from 165 percent to over 350 percent. In essence, the present welfare of the economy rests on debt, and the collateral for that debt consists of a wager that next year's levels of production and consumption will be higher than this year's. The Whole Growth/Debt Process is a Giant Ponzi Scheme About to Collapse Given that growth cannot continue on a finite planet, this wager, and its embodiment in the institutions of finance, can be said to constitute history's greatest Ponzi scheme. We have justified present borrowing with the irrational belief that perpetual growth is possible, necessary, and inevitable. In effect we have borrowed from future generations so that we could gamble away their capital today. Until recently, the Peak Oil argument has been framed as a forecast: the inevitable decline in world petroleum production, whenever it occurs, will kill growth. But here is where forecast becomes diagnosis: during the period from 2005 to 2008, energy stopped growing and oil prices rose to record levels. By July of 2008, the price of a barrel of oil was nudging close to $150—half again higher than any previous petroleum price in inflation-adjusted terms—and the global economy was beginning to topple. The auto and

airline industries shuddered; ordinary consumers had trouble buying gasoline for their commute to work while still paying their mortgages. Consumer spending began to decline. By September the economic crisis was also a financial crisis, as banks trembled and imploded. We Are Reaching Peak Everything and We Continue Our Addictive Compulsion for More Although some would hope we can make the transition to non-fossil fuel options and keep our economy expanding, Heinberg believes this is not possible. “My conclusion from a careful survey of energy alternatives,” says Heinberg, “is that there is little likelihood that either conventional fossil fuels or alternative energy sources can be counted on to provide the amount and quality of energy that will be needed to sustain economic growth—or even current levels of economic activity—during the remainder of this century.” He goes on to recognize that we are reaching our limits of more and more of the planets resources: The world's fresh water resources are strained to the point that billions of people may soon find themselves with only precarious access to water for drinking and irrigation. Biodiversity is declining rapidly. We are losing 24 billion tons of topsoil each year to erosion. And many economically significant minerals—from antimony to zinc— are depleting quickly, requiring the mining of ever lower-grade ores in ever more remote locations. Thus the Peak Oil crisis is really just the leading edge of a broader Peak Everything dilemma.

We Are Addicts on a Binge That Is Coming to An End Mind-active drugs are used by people in every culture throughout the world as long as humans have been on the planet. The pleasure centers in our brains make us susceptible to wanting more of whatever substances or experiences trigger those critical brain centers. In their book, Craving for Ecstasy: The Consciousness & Chemistry of Escape, psychologists Harvey Milkman and Stanley Sunderwirth describe the universal tendency we all have to become addicted. “We spend much of our lives in relentless pursuit of fleeting moments of exalted delight. But the consequences of compulsive pleasure seeking—whether through activities or use of substances—are often devastating.” Although most of us don’t immediately think of “oil” as an addictive substance, even though former President Bush declared that the nation was “addicted to oil.” However, when you recognize all the things we have become dependent upon during our fossil-fuel driven frenzy over the last 200 years, our dilemma becomes clearer. Think of the human race on the planet for millions of years, subsisting on renewable energy from the sun and living in balance with nature. All of a sudden we discover a source of energy (oil) that gives us hundreds and thousand times the amount of pleasure that we could generate up to that point. It’s not surprising that we have gone on a 200 year binge that it inevitably coming to an end. In his book, The Party’s Over: Oil, War, and the Fate of Industrial Societies, Heinberg, says, “It is as if part of the human race has been given a sudden windfall of wealth and decided to spend that wealth by throwing an extravagant party. The party has not been without its discontents or costs. From time to time, a lone voice issuing from here or there has called for the party to quiet down or cease altogether. The partiers have

paid no attention. But soon the part itself will be a fading memory—not because anyone decided to heed the voice of moderation, but because the wine and food are gone and the harsh light of morning has come. Every Addicts Dilemma: Get Clean or Die In the 40 years I have treated addicts of every kind I know that no matter how destructive their addiction has been, they have within them a tremendous resiliency and desire to recover. Most addicts have to reach their own bottom. As long as there still drugs available, as long as they have some money to buy some form of escape, they keep trying. I say that addicts want to go home, but like confused homing pigeons, they continue to fly 180 degrees in the wrong direction. But addicts do recover. Most of them do it by acknowledging that they have become addicted, and reaching out to other addicts for help and support, meeting in local groups in communities throughout the world. It would be nice if those in power paid more than lip service to our addiction to oil, but we don’t have to wait until they do to begin our own recovery program. As Heinberg says, “Even if policy makers continue to ignore warnings, individuals and communities can take heed and begin the process of building resilience, and of detaching themselves from reliance on fossil fuels and institutions that are inextricably tied to the perpetual growth machine. We cannot sit passively by as world leaders squander opportunities to awaken and adapt to growth limits. We can make changes in our own lives, and we can join with our neighbors. And we can let policy makers know we disapprove of their allegiance to the status quo, but that there are other options.”

“Is it too late to begin a managed transition to a post-fossil fuel society?” Heinberg asks. “Perhaps, but we will not know unless we try. And if we are to make that effort, we must begin by acknowledging one simple, stark reality: growth as we have known it can no longer be our goal.” As we begin our own recovery, we just reject the notion that someone else is to blame for our situation. It isn’t President Obama. It isn’t the Republicans. It isn’t foreign “terrorists.” As the great philosopher Pogo remarked, “We have met the enemy and he is us.” We might remind ourselves, too, that we have met the hope for the future and that is us as well. Jed Diamond, Ph.D. Resources: www.RichardHeinberg.com www.PostCarbon.org www.TransitionUS.org

Let’s face it, no matter what the latest ups and downs we read in the news, the economy is still sick. And predictably President Obama’s approval ratings are dropping. When he was elected most of the world felt hopeful that Mr. Obama could make a difference and turn things around within the country and with our relationships around the world. Democrats were looking forward to major changes in health reform and an end to the dysfunctional economic policies of the Bush years. Republicans were worried that Obama would change America in a way not to their liking. All felt he was destined to have a major impact on our lives. I think he has and he will. It’s great to have a man who is charismatic, intelligent, thoughtful, willing to work with disparate groups, and a man who seeks reconciliation rather than conflict. But I’m afraid the nature of the problems we face are not going to be solved by even the most intelligent, hard-working, and dedicated President. If we

recognize that we can hope for the best, but be prepared for the worst, and resist the temptation to make the President the scapegoat for our unfilled expectations, we will be able to take responsibility for creating the kind of country and world we truly want and need. For those a bit rusty on their biblical history, in Leviticus, the scapegoat is loaded own with the sins to which the ancient Israelites have confessed and then banished into the wilderness. The word "scapegoat" has come to mean a person, often innocent, who is blamed and punished for the sins, crimes, or sufferings of others, generally as a way of distracting attention from the real causes. Most of us have been “scapegoated” in our lives and it’s not very comfortable. It order to prevent this from happening to President Obama (or anyone else) we have to get a clearer picture of the nature of our economic ills and what the true causes of failure might be. So why are both the U.S. economy and the larger global economy ailing? Those in positions of power, i.e. the mainstream media, world leaders, and America’s chief economists, Treasury Secretary Geithner and Feberal Reserve Chairman Bernanke) offer near unanimity in their opinion: Those recent troubles are temporary and are primarily due to a combination of bad real estate loans and poor regulation of financial derivatives. As a health-care practitioner, I know how important it is to have the correct diagnosis of an illness if treatment is to be most effective. If this conventional diagnosis is correct, then the treatment of our economic malady might logically include heavy doses of bailout money for beleaguered financial institutions, mortgage lenders, and car companies. Plus

better regulation of derivatives and futures markets. And finally, stimulus programs to jumpstart consumer spending. But Richard Heinberg, a fellow at the Post Carbon Institute, and a man I have learned to respect greatly over the years (not the least because he usually turns out to be right), has a different take on what ails us. “I am suggesting an Alternative Diagnosis,” says Heinberg. “This explanation for the economic crisis is not for the faint of heart because, if correct, it implies that the patient is far sicker than even the most pessimistic economists are telling us. But if it is correct, then by ignoring it we risk even greater peril.” When James Howard Kunstler wrote The Long Emergency in 2005, he said that the greatest danger this society faced would be its inclination to gear up a campaign to sustain the unsustainable at all costs -- rather than face the need to make new arrangements for daily life. This seems to be what is happening at the top levels of power. Peak Oil and the Limits of Growth For several years, a swelling subculture of commentators (which includes Heinberg, Matt Savinar, Carolyn Baker, James Howard Kunstler, and others) have been forecasting a financial crash, basing this prognosis on the assessment that global oil production was about to peak. As summarized by Heinberg in his August, 2009 Museletter (www.RichardHeinberg.com), their reasoning went like this: Continual increases in population and consumption cannot continue forever on a finite planet. This is an axiomatic observation with which everyone familiar with the

mathematics of compounded arithmetic growth must agree, even if they hedge their agreement with vague references to "substitutability" and "demographic transitions." Energy is the ultimate enabler of growth (again, this is axiomatic: physics and biology both tell us that without energy nothing happens). Industrial expansion throughout the past two centuries has in every instance been based on increased energy consumption. More specifically, industrialism has been inextricably tied to the availability and consumption of cheap energy from coal and oil (and more recently, natural gas). However, fossil fuels are by their very nature depleting, non-renewable resources. Therefore (according to the Peak Oil thesis), the eventual inability to continue increasing supplies of cheap fossil energy will likely lead to a cessation of economic growth in general, unless alternative energy sources and efficiency of energy use can be deployed rapidly and to a sufficient degree. Of the three conventional fossil fuels, oil is arguably the most economically vital, since it supplies 95 percent of all transport energy. Further, petroleum is the fuel with which we are likely to encounter supply problems soonest, because global petroleum discoveries have been declining for decades, and most oil producing countries are already seeing production declines. So, by this logic, the end of economic growth (as conventionally defined) is inevitable, and Peak Oil is the likely trigger. Increased Growth Leads to Increased Debt Which Can No Longer Be Serviced Why would Peak Oil lead not just to problems for the transport industry, but a more general economic and financial crisis? During the past century growth has become institutionalized in the very sinews of our economic system. Every city and business wants to grow. This is understandable merely in terms of human nature: nearly everyone

wants a competitive advantage over someone else, and growth provides the opportunity to achieve it. But there is also a financial survival motive at work: without growth, businesses and governments are unable to service their debt. And debt has become endemic to the industrial system. During the past couple of decades, the financial services industry has grown faster than any other sector of the American economy, even outpacing the rise in health care expenditures, accounting for a third of all growth in the U.S. economy. From 1990 to the present, the ratio of debt-to-GDP expanded from 165 percent to over 350 percent. In essence, the present welfare of the economy rests on debt, and the collateral for that debt consists of a wager that next year's levels of production and consumption will be higher than this year's. The Whole Growth/Debt Process is a Giant Ponzi Scheme About to Collapse Given that growth cannot continue on a finite planet, this wager, and its embodiment in the institutions of finance, can be said to constitute history's greatest Ponzi scheme. We have justified present borrowing with the irrational belief that perpetual growth is possible, necessary, and inevitable. In effect we have borrowed from future generations so that we could gamble away their capital today. Until recently, the Peak Oil argument has been framed as a forecast: the inevitable decline in world petroleum production, whenever it occurs, will kill growth. But here is where forecast becomes diagnosis: during the period from 2005 to 2008, energy stopped growing and oil prices rose to record levels. By July of 2008, the price of a barrel of oil was nudging close to $150—half again higher than any previous petroleum price in inflation-adjusted terms—and the global economy was beginning to topple. The auto and

airline industries shuddered; ordinary consumers had trouble buying gasoline for their commute to work while still paying their mortgages. Consumer spending began to decline. By September the economic crisis was also a financial crisis, as banks trembled and imploded. We Are Reaching Peak Everything and We Continue Our Addictive Compulsion for More Although some would hope we can make the transition to non-fossil fuel options and keep our economy expanding, Heinberg believes this is not possible. “My conclusion from a careful survey of energy alternatives,” says Heinberg, “is that there is little likelihood that either conventional fossil fuels or alternative energy sources can be counted on to provide the amount and quality of energy that will be needed to sustain economic growth—or even current levels of economic activity—during the remainder of this century.” He goes on to recognize that we are reaching our limits of more and more of the planets resources: The world's fresh water resources are strained to the point that billions of people may soon find themselves with only precarious access to water for drinking and irrigation. Biodiversity is declining rapidly. We are losing 24 billion tons of topsoil each year to erosion. And many economically significant minerals—from antimony to zinc— are depleting quickly, requiring the mining of ever lower-grade ores in ever more remote locations. Thus the Peak Oil crisis is really just the leading edge of a broader Peak Everything dilemma.

We Are Addicts on a Binge That Is Coming to An End Mind-active drugs are used by people in every culture throughout the world as long as humans have been on the planet. The pleasure centers in our brains make us susceptible to wanting more of whatever substances or experiences trigger those critical brain centers. In their book, Craving for Ecstasy: The Consciousness & Chemistry of Escape, psychologists Harvey Milkman and Stanley Sunderwirth describe the universal tendency we all have to become addicted. “We spend much of our lives in relentless pursuit of fleeting moments of exalted delight. But the consequences of compulsive pleasure seeking—whether through activities or use of substances—are often devastating.” Although most of us don’t immediately think of “oil” as an addictive substance, even though former President Bush declared that the nation was “addicted to oil.” However, when you recognize all the things we have become dependent upon during our fossil-fuel driven frenzy over the last 200 years, our dilemma becomes clearer. Think of the human race on the planet for millions of years, subsisting on renewable energy from the sun and living in balance with nature. All of a sudden we discover a source of energy (oil) that gives us hundreds and thousand times the amount of pleasure that we could generate up to that point. It’s not surprising that we have gone on a 200 year binge that it inevitably coming to an end. In his book, The Party’s Over: Oil, War, and the Fate of Industrial Societies, Heinberg, says, “It is as if part of the human race has been given a sudden windfall of wealth and decided to spend that wealth by throwing an extravagant party. The party has not been without its discontents or costs. From time to time, a lone voice issuing from here or there has called for the party to quiet down or cease altogether. The partiers have

paid no attention. But soon the part itself will be a fading memory—not because anyone decided to heed the voice of moderation, but because the wine and food are gone and the harsh light of morning has come. Every Addicts Dilemma: Get Clean or Die In the 40 years I have treated addicts of every kind I know that no matter how destructive their addiction has been, they have within them a tremendous resiliency and desire to recover. Most addicts have to reach their own bottom. As long as there still drugs available, as long as they have some money to buy some form of escape, they keep trying. I say that addicts want to go home, but like confused homing pigeons, they continue to fly 180 degrees in the wrong direction. But addicts do recover. Most of them do it by acknowledging that they have become addicted, and reaching out to other addicts for help and support, meeting in local groups in communities throughout the world. It would be nice if those in power paid more than lip service to our addiction to oil, but we don’t have to wait until they do to begin our own recovery program. As Heinberg says, “Even if policy makers continue to ignore warnings, individuals and communities can take heed and begin the process of building resilience, and of detaching themselves from reliance on fossil fuels and institutions that are inextricably tied to the perpetual growth machine. We cannot sit passively by as world leaders squander opportunities to awaken and adapt to growth limits. We can make changes in our own lives, and we can join with our neighbors. And we can let policy makers know we disapprove of their allegiance to the status quo, but that there are other options.”

“Is it too late to begin a managed transition to a post-fossil fuel society?” Heinberg asks. “Perhaps, but we will not know unless we try. And if we are to make that effort, we must begin by acknowledging one simple, stark reality: growth as we have known it can no longer be our goal.” As we begin our own recovery, we just reject the notion that someone else is to blame for our situation. It isn’t President Obama. It isn’t the Republicans. It isn’t foreign “terrorists.” As the great philosopher Pogo remarked, “We have met the enemy and he is us.” We might remind ourselves, too, that we have met the hope for the future and that is us as well. Jed Diamond, Ph.D. Resources: www.RichardHeinberg.com www.PostCarbon.org www.TransitionUS.org

Related Documents

Obama President

July 2020 12

Letter To President Obama On The Economy

June 2020 9

President Obama Inauguration Speech

May 2020 20

(2009) President Obama Inauguration

May 2020 13