Determination Of Death In Children

This document was uploaded by user and they confirmed that they have the permission to share it. If you are author or own the copyright of this book, please report to us by using this DMCA report form. Report DMCA

Overview

Download & View Determination Of Death In Children as PDF for free.

More details

- Words: 2,956

- Pages: 4

3B Med ethics MARY YVETTE ALLAIN TINA RALPH SHERYL BART HEINRICH PIPOY TLE JAM CECILLE DENESSE VINCE HOOPS CES XTIAN LAINEY RIZ KIX EZRA GOLDIE BUFF MONA AM MAAN ADI KC PENG KARLA ALPHE AARON KYTH ANNE EISA KRING CANDY ISAY MARCO JOSHUA FARS RAIN JASSIE MIKA SHAR ERIKA MAQUI VIKI JOAN PREI KATE BAM AMS HANNAH MEMAY PAU RACHE ESTHER JOEL GLENN TONI

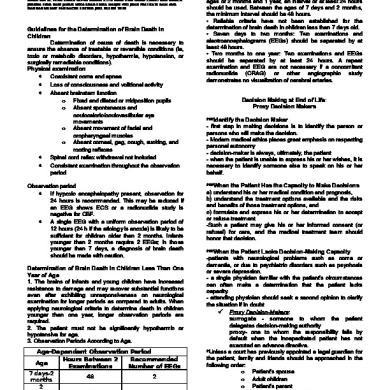

Guidelines for the Determination of Brain Death in Children Determination of cause of death is necessary to ensure the absence of treatable or reversible conditions (ie, toxic or metabolic disorders, hypothermia, hypotension, or surgically remediable conditions). Physical examination • Coexistent coma and apnea • Loss of consciousness and volitional activity • Absent brainstem function o Fixed and dilated or midposition pupils o Absent spontaneous and oculocaloric/oculovestibular eye movements o Absent movement of facial and oropharyngeal muscles o Absent corneal, gag, cough, sucking, and rooting reflexes • Spinal cord reflex withdrawal not included • Consistent examination throughout the observation period Observation period • If hypoxic encephalopathy present, observation for 24 hours is recommended. This may be reduced if an EEG shows ECS or a radionuclide study is negative for CBF. • A single EEG with a uniform observation period of 12 hours (24 h if the etiology is anoxia) is likely to be sufficient for children older than 2 months. Infants younger than 2 months require 2 EEGs; in those younger than 7 days, a diagnosis of brain death should be made with caution. Determination of Brain Death In Children Less Than One Year of Age 1. The brains of infants and young children have increased resistance to damage and may recover substantial functions even after exhibiting unresponsiveness on neurological examination for longer periods as compared to adults. When applying neurological criteria to determine death in children younger than one year, longer observation periods are required. 2. The patient must not be significantly hypothermic or hypotensive for age. 3. Observation Periods According to Age. Age-Dependent Observation Period Hours Between 2 Recommended Age Examinations Number of EEGs 7 days-2 48 2 months 2 months-1 24 2 year >1 year 12 Not needed

The recommended observation period depends on the age of the patient and the laboratory tests utilized. Ages listed assume the child was born at full term. Between the ages of 2 months and 1 year, an interval of at least 24 hours should be used. Between the ages of 7 days and 2 months, the minimum interval should be 48 hours. • Reliable criteria have not been established for the determination of brain death in children less than 7 days old. • Seven days to two months: Two examinations and electroencephalograms (EEGs) should be separated by at least 48 hours. • Two months to one year: Two examinations and EEGs should be separated by at least 24 hours. A repeat examination and EEG are not necessary if a concomitant radionuclide (CRAG) or other angiographic study demonstrates no visualization of cerebral arteries. Decision Making at End of Life: Proxy Decision Makers ***Identify the Decision Maker - first step in making decisions is to identify the person or persons who will make the decision. - Modern medical ethics places great emphasis on respecting personal autonomy - decision-maker is always, ultimately, the patient - when the patient is unable to express his or her wishes, it is necessary to identify someone else to speak on his or her behalf. ***When the Patient Has the Capacity to Make Decisions a) understand his or her medical condition and prognosis, b) understand the treatment options available and the risks and benefits of those treatment options, and c) formulate and express his or her determination to accept or refuse treatment. -Such a patient may give his or her informed consent (or refusal) for care, and the medical treatment team should honor that decision. ***When the Patient Lacks Decision-Making Capacity -patients with neurological problems such as coma or dementia, or due to psychiatric disorders such as psychosis or severe depression. - a single physician familiar with the patient's circumstances can often make a determination that the patient lacks capacity. - attending physician should seek a second opinion to clarify the situation if in doubt Proxy Decision-Makers: surrogate - someone to whom the patient delegates decision-making authority proxy- one to whom the responsibility falls by default when the incapacitated patient has not executed an advance directive. *Unless a court has previously appointed a legal guardian for the patient, family and friends should be approached in the following order: o Patient's spouse o Adult children o Patient's parent o Adult siblings of patient o Adult relative who is familiar with the patient's values and beliefs

o Close friend of the patient substituted judgement -proxies should make the decision they believe the patient would make if he or she could speak for himself or herself, based on their knowledge of the patient and his or her value system. -When there is more than one adult child or sibling and they disagree about what the patient would want, care should be provided according to the directions of the majority of those available to participate in the decision-making process. Proxy and Surrogate Decisions Should Be the Decisions the Patient Would Make - correct question with which to begin discussions of end-oflife care is, "What do you think your loved one would want us to do?" This allows the family to reflect on what the patient considered important in life and to say, as is often the case, "She would never have wanted to be kept alive like this."

Substituted judgment for incompetent patients -When a patient has lost the mental capacity to make decisions, caregivers should attempt to reconstruct the patient's values and philosophies to make decisions as the patient would if able to comprehend the medical situation and options available. - proxy decision maker's role is not to express what they would want for the patient or for themselves but what the patient would want. -Only when no clue exists to what the patient would have decided should a generic view of the patient's “best interests” be invoked.

Children’s role in decision-making: - Children live in their own reality. - Developmental concepts of death change over time. - Capacity to participate in decisions changes over time. - Some children have no capacity to participate in decisions (infants through preschool, or children who are neurologically devastated), some have developing capacity to participate in decisions (those in elementary school), and many have achieved capacity to make decisions concerning their care (adolescents, mature minors, and emancipated minors among others). - Children may achieve the ability to participate in decisions earlier than is recognized legally: We should respect the fact that children with chronic diseases seem to have an advanced sense of understanding of their condition, and ownership and mastery over their disease. -Central to good, appropriate decision making is determining what is in the best interest of the child, from the child's viewpoint. -Parents are traditionally considered as proxy decision makers on behalf of the child. However, parents do not always act in the best interest of the child and there may even be conflicts of interest. - concept of informed parental permission better describes the parental role. -If we are to respect the child's autonomy, we should involve any child able to participate in decision making. -Although children as young as 7-8 years are asked to provide assent, we can be surprised that they can competently engineer the environment surrounding their death. - For very young children, the parents might direct treatment decisions, guided by the health care team.

- For children with developing capacity, the child in partnership with the parents and medical team should make decisions. - All children with full decisional capacity have the right to make decisions about their treatment or nontreatment. - Decisions should be made with parental and medical advice and counseling. - child should have a reasonable understanding of his or her illness, the treatment options including benefits and burdens of treatment, and the consequences of treatment options. - child should be able to make a decision that reflects his or her own values and be able to communicate the decision to caregivers. - decision requires assessment of each child participating in each individual decision. -Age alone can rarely be used as an indication of competence. - If children are determined to be competent, health care providers should not only seek their assent to treatment plans but also accept their dissent. ***Role of the health care provider - health care team provides accurate information about diagnosis, prognosis, disease course, treatment options, and consequences of the options including nontreatment. -Together with the child and family they identify goals, values, and expectations. - team assists the family and child in selecting an appropriate treatment plan, from among medically and ethically appropriate options. - Only those choices should be offered that meet the goals of treatment and are in the child's best interest. - It is important for the health care team to accept responsibility for helping the child/family choose an appropriate course of action. - In cases of uncertainty, the most useful approach to decision making often involves a time-limited trial of a proposed treatment or treatments. - Beneficial treatments are continued. - Interventions with lack of benefit or excessive burden are withdrawn or not instituted. Summary we can help the child at end of life come to an awareness of her/his disease and a new reality. First we must acknowledge that we cannot always protect children from death. We can, however, help the child and family identify their goals and select a treatment plan that meets their goals and is in the child's best interest. A family-centered decision-making approach respects the complex nature of the parent-child relationship, the dependence and vulnerability of the child, and the emerging ability of the child to participate in decision making. The key components are o child assent, o parental permission and guidance o acceptance of the developing capacity of the child as decision maker. developing child gradually displaces the parents as the partner in decision making about health care. We can respect children's autonomy, allow them to care for themselves and participate in decision making, and take control of their dying.

•

Regardless of whether the goal is prolonging life or primarily comfort, excellent palliative or supportive care must be provided to the child and family. Children belong to themselves. They must be trusted to manage their own dying. When to Use Institutional and Legal Measures

Ethics Advisory Committee Consultation •

•

•

If significant disagreement persists after efforts to improve communication Some disagreements are not disagreements about facts but about values, and such a consultation can help to clarify which values are in conflict. Ethics Advisory Committees serve an advisory role, facilitating communication and assisting those involved in thinking through the ethical issues of the situation.

Recourse to the Legal System all less burdensome measures to resolve disagreements have failed, it may become necessary to turn to the courts for a resolution. focus has shifted from identifying the right thing to do to defining the legal thing to do. most jurisdictions would prefer that such questions be resolved in collaborative discussions among physicians, patients and families. Informed consent Informed consent in end-of-life care is important for 2 reasons beyond the fact that it is a basic legal and ethical requirement for all medical interventions. First, many patients and families (or parents if the patient is a child) who are facing treatment withdrawal may not have been fully informed of the risks and benefits of the therapy at the time it was begun, nor, often, were they told that treatment would be withdrawn if the treatment was no longer effective. Second, patients and families who refuse further treatment should be told the consequences of the discontinuation of treatment, just as they are told the benefits and risks of other interventions. Reasonable information giving is judged partly by the standards of what any good professional would give and what any reasonable person would want in the same circumstances. Advance Directives

•

Advance directives are written instructions which communicate the wishes about the care and treatment that a patient want to receive if they reach the point they can no longer speak for themselves.

•

Probably the most commonly used form of advance directive is the durable power of attorney for health care. A more limited type of advance directive is the living will.

durable power of attorney for health care (also called the "medical power of attorney")

• • • •

names someone, a relative or friend to make medical decisions for the patient. designated person is called an agent, attorney-infact, proxy, or surrogate. deals with all medical decisions unless they decide to limit it. Specific instructions can be given about treatments and other concerns. must be signed to be valid.

The living will, in some called "instructions," "directive to physicians," or "declaration,"

• •

states your their desires regarding life-sustaining or life-prolonging medical treatment. generally apply to specific circumstances that may arise near the end of your life, such as prolonged unconsciousness.

Other forms or methods of instruction may also be available to you, including:

•

•

A Do Not Resuscitate or DNR order, which instructs medical personnel, including emergency medical personnel, not to use resuscitative measures. A preferred intensity of care document, a form for your physician that outlines your preferences for care under special circumstances.

DISAGREEMENTS between FAMILY and PHYSICIAN Disagreement between patients/families and health care professionals about treatment decisions ranked #1 in the Top 10 Ethical Challenges in Health Care. (Breslin, University of Toronto Joint Care for Bioethics study) One of the most difficult situations physicians face is how to handle conflicts with families over forgoing lifesustaining treatment. The biggest issue in medical ethics today is the growing occurrence of conflict between health care providers, their patients and patients' families over treatment options. Physicians may feel their competence or judgment is not trusted and turn to legal or ethics consultants for help with what they feel is a wrong decision by the patient or the patient's proxy decision-maker. Families may feel isolated, misunderstood, or abandoned and begin to doubt the healthcare team's commitment to the patient's well-being. What should be a

cooperative effort to achieve goals can turn into an exercise in frustration and distress. Most common pitfalls in establishing plans of care for patients who lack decision-making capacity include: failure to reach a shared appreciation of the patient's condition and prognosis; failure to apply the principle of substituted judgment; offering the choice between care and no care, rather than offering the choice between prolonging life and quality of life; too literal an interpretation of an isolated, out-of-context, patient statement made earlier in life; failure to address the full range of end-of-life decisions from do-not-resuscitate orders to exclusive palliative care. Reasons why a family member or patient's proxy may not understand the medical facts are:

The family or patient's proxy may be psychologically

unprepared to hear the patient's diagnosis or prognosis "Bad news" is often poorly processed and imperfectly remembered Sometimes a physician's communication style increases misunderstanding Families obtain information from multiple sources (TV, Internet, friends and relatives) There may be a gap between the physicians' values and those of patients or their families

A number of physician characteristics that contribute to conflicts regarding end-of-life decisions include:

Physicians, like patients, also may be uncomfortable with prognostic uncertainty Physicians may be uncomfortable discussing death or be troubled by the thought of a medical "failure" Physicians tend to underestimate chronically ill patients' quality of life, and are more likely than patients or families to think such patients would choose to forgo life-sustaining treatment Religious or philosophical beliefs about the sanctity of life Beliefs and attitudes regarding the proper role of families and proxies in the end-of-life care decisionmaking process Difficulty dealing with the different value systems of others Physicians may be insecure about limitations of their own competency or skill Physicians may be unaware of prognosis or treatment options and misinform the family or patient's proxy Physicians may not understand ethical, legal, or hospital policies regarding end-of-life care A lack of training in symptom management may lead to inappropriate care Physicians may be ill-trained in interpersonal communication regarding end-of-life care decisions, leading to misunderstandings, confusion, and frustrations

The culture of the hospital may lead to "high-tech" interventions and avoidance of time-consuming conferences with family member

To improve decision making for critically ill patients: First, given the high levels of conflict and the variability in perception of conflict among different staff members, clinicians should strive to recognize conflict so that it can be dealt with constructively. Second, many of the disagreements we identified were not caused directly by different opinions about limiting treatment. Physicians facing a conflict-filled situation should try to determine whether the conflict is actually rooted in a difference of opinion about life-sustaining treatment, or whether it is caused by miscommunication, personality conflict, or unaddressed emotional or social issues. Efforts can then be directed at resolving the particular issue at hand. Third, health care providers should try to identify potentially conflict-ridden situations to prevent discord. Keeping families informed about the patient's response to therapy and what treatment options remain throughout a patient's illness may reduce the likelihood that families will be “blind-sided” by a request to limit treatment. “Preventive ethics” may help avert unproductive conflict and needlessly difficult decisions

Guidelines for the Determination of Brain Death in Children Determination of cause of death is necessary to ensure the absence of treatable or reversible conditions (ie, toxic or metabolic disorders, hypothermia, hypotension, or surgically remediable conditions). Physical examination • Coexistent coma and apnea • Loss of consciousness and volitional activity • Absent brainstem function o Fixed and dilated or midposition pupils o Absent spontaneous and oculocaloric/oculovestibular eye movements o Absent movement of facial and oropharyngeal muscles o Absent corneal, gag, cough, sucking, and rooting reflexes • Spinal cord reflex withdrawal not included • Consistent examination throughout the observation period Observation period • If hypoxic encephalopathy present, observation for 24 hours is recommended. This may be reduced if an EEG shows ECS or a radionuclide study is negative for CBF. • A single EEG with a uniform observation period of 12 hours (24 h if the etiology is anoxia) is likely to be sufficient for children older than 2 months. Infants younger than 2 months require 2 EEGs; in those younger than 7 days, a diagnosis of brain death should be made with caution. Determination of Brain Death In Children Less Than One Year of Age 1. The brains of infants and young children have increased resistance to damage and may recover substantial functions even after exhibiting unresponsiveness on neurological examination for longer periods as compared to adults. When applying neurological criteria to determine death in children younger than one year, longer observation periods are required. 2. The patient must not be significantly hypothermic or hypotensive for age. 3. Observation Periods According to Age. Age-Dependent Observation Period Hours Between 2 Recommended Age Examinations Number of EEGs 7 days-2 48 2 months 2 months-1 24 2 year >1 year 12 Not needed

The recommended observation period depends on the age of the patient and the laboratory tests utilized. Ages listed assume the child was born at full term. Between the ages of 2 months and 1 year, an interval of at least 24 hours should be used. Between the ages of 7 days and 2 months, the minimum interval should be 48 hours. • Reliable criteria have not been established for the determination of brain death in children less than 7 days old. • Seven days to two months: Two examinations and electroencephalograms (EEGs) should be separated by at least 48 hours. • Two months to one year: Two examinations and EEGs should be separated by at least 24 hours. A repeat examination and EEG are not necessary if a concomitant radionuclide (CRAG) or other angiographic study demonstrates no visualization of cerebral arteries. Decision Making at End of Life: Proxy Decision Makers ***Identify the Decision Maker - first step in making decisions is to identify the person or persons who will make the decision. - Modern medical ethics places great emphasis on respecting personal autonomy - decision-maker is always, ultimately, the patient - when the patient is unable to express his or her wishes, it is necessary to identify someone else to speak on his or her behalf. ***When the Patient Has the Capacity to Make Decisions a) understand his or her medical condition and prognosis, b) understand the treatment options available and the risks and benefits of those treatment options, and c) formulate and express his or her determination to accept or refuse treatment. -Such a patient may give his or her informed consent (or refusal) for care, and the medical treatment team should honor that decision. ***When the Patient Lacks Decision-Making Capacity -patients with neurological problems such as coma or dementia, or due to psychiatric disorders such as psychosis or severe depression. - a single physician familiar with the patient's circumstances can often make a determination that the patient lacks capacity. - attending physician should seek a second opinion to clarify the situation if in doubt Proxy Decision-Makers: surrogate - someone to whom the patient delegates decision-making authority proxy- one to whom the responsibility falls by default when the incapacitated patient has not executed an advance directive. *Unless a court has previously appointed a legal guardian for the patient, family and friends should be approached in the following order: o Patient's spouse o Adult children o Patient's parent o Adult siblings of patient o Adult relative who is familiar with the patient's values and beliefs

o Close friend of the patient substituted judgement -proxies should make the decision they believe the patient would make if he or she could speak for himself or herself, based on their knowledge of the patient and his or her value system. -When there is more than one adult child or sibling and they disagree about what the patient would want, care should be provided according to the directions of the majority of those available to participate in the decision-making process. Proxy and Surrogate Decisions Should Be the Decisions the Patient Would Make - correct question with which to begin discussions of end-oflife care is, "What do you think your loved one would want us to do?" This allows the family to reflect on what the patient considered important in life and to say, as is often the case, "She would never have wanted to be kept alive like this."

Substituted judgment for incompetent patients -When a patient has lost the mental capacity to make decisions, caregivers should attempt to reconstruct the patient's values and philosophies to make decisions as the patient would if able to comprehend the medical situation and options available. - proxy decision maker's role is not to express what they would want for the patient or for themselves but what the patient would want. -Only when no clue exists to what the patient would have decided should a generic view of the patient's “best interests” be invoked.

Children’s role in decision-making: - Children live in their own reality. - Developmental concepts of death change over time. - Capacity to participate in decisions changes over time. - Some children have no capacity to participate in decisions (infants through preschool, or children who are neurologically devastated), some have developing capacity to participate in decisions (those in elementary school), and many have achieved capacity to make decisions concerning their care (adolescents, mature minors, and emancipated minors among others). - Children may achieve the ability to participate in decisions earlier than is recognized legally: We should respect the fact that children with chronic diseases seem to have an advanced sense of understanding of their condition, and ownership and mastery over their disease. -Central to good, appropriate decision making is determining what is in the best interest of the child, from the child's viewpoint. -Parents are traditionally considered as proxy decision makers on behalf of the child. However, parents do not always act in the best interest of the child and there may even be conflicts of interest. - concept of informed parental permission better describes the parental role. -If we are to respect the child's autonomy, we should involve any child able to participate in decision making. -Although children as young as 7-8 years are asked to provide assent, we can be surprised that they can competently engineer the environment surrounding their death. - For very young children, the parents might direct treatment decisions, guided by the health care team.

- For children with developing capacity, the child in partnership with the parents and medical team should make decisions. - All children with full decisional capacity have the right to make decisions about their treatment or nontreatment. - Decisions should be made with parental and medical advice and counseling. - child should have a reasonable understanding of his or her illness, the treatment options including benefits and burdens of treatment, and the consequences of treatment options. - child should be able to make a decision that reflects his or her own values and be able to communicate the decision to caregivers. - decision requires assessment of each child participating in each individual decision. -Age alone can rarely be used as an indication of competence. - If children are determined to be competent, health care providers should not only seek their assent to treatment plans but also accept their dissent. ***Role of the health care provider - health care team provides accurate information about diagnosis, prognosis, disease course, treatment options, and consequences of the options including nontreatment. -Together with the child and family they identify goals, values, and expectations. - team assists the family and child in selecting an appropriate treatment plan, from among medically and ethically appropriate options. - Only those choices should be offered that meet the goals of treatment and are in the child's best interest. - It is important for the health care team to accept responsibility for helping the child/family choose an appropriate course of action. - In cases of uncertainty, the most useful approach to decision making often involves a time-limited trial of a proposed treatment or treatments. - Beneficial treatments are continued. - Interventions with lack of benefit or excessive burden are withdrawn or not instituted. Summary we can help the child at end of life come to an awareness of her/his disease and a new reality. First we must acknowledge that we cannot always protect children from death. We can, however, help the child and family identify their goals and select a treatment plan that meets their goals and is in the child's best interest. A family-centered decision-making approach respects the complex nature of the parent-child relationship, the dependence and vulnerability of the child, and the emerging ability of the child to participate in decision making. The key components are o child assent, o parental permission and guidance o acceptance of the developing capacity of the child as decision maker. developing child gradually displaces the parents as the partner in decision making about health care. We can respect children's autonomy, allow them to care for themselves and participate in decision making, and take control of their dying.

•

Regardless of whether the goal is prolonging life or primarily comfort, excellent palliative or supportive care must be provided to the child and family. Children belong to themselves. They must be trusted to manage their own dying. When to Use Institutional and Legal Measures

Ethics Advisory Committee Consultation •

•

•

If significant disagreement persists after efforts to improve communication Some disagreements are not disagreements about facts but about values, and such a consultation can help to clarify which values are in conflict. Ethics Advisory Committees serve an advisory role, facilitating communication and assisting those involved in thinking through the ethical issues of the situation.

Recourse to the Legal System all less burdensome measures to resolve disagreements have failed, it may become necessary to turn to the courts for a resolution. focus has shifted from identifying the right thing to do to defining the legal thing to do. most jurisdictions would prefer that such questions be resolved in collaborative discussions among physicians, patients and families. Informed consent Informed consent in end-of-life care is important for 2 reasons beyond the fact that it is a basic legal and ethical requirement for all medical interventions. First, many patients and families (or parents if the patient is a child) who are facing treatment withdrawal may not have been fully informed of the risks and benefits of the therapy at the time it was begun, nor, often, were they told that treatment would be withdrawn if the treatment was no longer effective. Second, patients and families who refuse further treatment should be told the consequences of the discontinuation of treatment, just as they are told the benefits and risks of other interventions. Reasonable information giving is judged partly by the standards of what any good professional would give and what any reasonable person would want in the same circumstances. Advance Directives

•

Advance directives are written instructions which communicate the wishes about the care and treatment that a patient want to receive if they reach the point they can no longer speak for themselves.

•

Probably the most commonly used form of advance directive is the durable power of attorney for health care. A more limited type of advance directive is the living will.

durable power of attorney for health care (also called the "medical power of attorney")

• • • •

names someone, a relative or friend to make medical decisions for the patient. designated person is called an agent, attorney-infact, proxy, or surrogate. deals with all medical decisions unless they decide to limit it. Specific instructions can be given about treatments and other concerns. must be signed to be valid.

The living will, in some called "instructions," "directive to physicians," or "declaration,"

• •

states your their desires regarding life-sustaining or life-prolonging medical treatment. generally apply to specific circumstances that may arise near the end of your life, such as prolonged unconsciousness.

Other forms or methods of instruction may also be available to you, including:

•

•

A Do Not Resuscitate or DNR order, which instructs medical personnel, including emergency medical personnel, not to use resuscitative measures. A preferred intensity of care document, a form for your physician that outlines your preferences for care under special circumstances.

DISAGREEMENTS between FAMILY and PHYSICIAN Disagreement between patients/families and health care professionals about treatment decisions ranked #1 in the Top 10 Ethical Challenges in Health Care. (Breslin, University of Toronto Joint Care for Bioethics study) One of the most difficult situations physicians face is how to handle conflicts with families over forgoing lifesustaining treatment. The biggest issue in medical ethics today is the growing occurrence of conflict between health care providers, their patients and patients' families over treatment options. Physicians may feel their competence or judgment is not trusted and turn to legal or ethics consultants for help with what they feel is a wrong decision by the patient or the patient's proxy decision-maker. Families may feel isolated, misunderstood, or abandoned and begin to doubt the healthcare team's commitment to the patient's well-being. What should be a

cooperative effort to achieve goals can turn into an exercise in frustration and distress. Most common pitfalls in establishing plans of care for patients who lack decision-making capacity include: failure to reach a shared appreciation of the patient's condition and prognosis; failure to apply the principle of substituted judgment; offering the choice between care and no care, rather than offering the choice between prolonging life and quality of life; too literal an interpretation of an isolated, out-of-context, patient statement made earlier in life; failure to address the full range of end-of-life decisions from do-not-resuscitate orders to exclusive palliative care. Reasons why a family member or patient's proxy may not understand the medical facts are:

The family or patient's proxy may be psychologically

unprepared to hear the patient's diagnosis or prognosis "Bad news" is often poorly processed and imperfectly remembered Sometimes a physician's communication style increases misunderstanding Families obtain information from multiple sources (TV, Internet, friends and relatives) There may be a gap between the physicians' values and those of patients or their families

A number of physician characteristics that contribute to conflicts regarding end-of-life decisions include:

Physicians, like patients, also may be uncomfortable with prognostic uncertainty Physicians may be uncomfortable discussing death or be troubled by the thought of a medical "failure" Physicians tend to underestimate chronically ill patients' quality of life, and are more likely than patients or families to think such patients would choose to forgo life-sustaining treatment Religious or philosophical beliefs about the sanctity of life Beliefs and attitudes regarding the proper role of families and proxies in the end-of-life care decisionmaking process Difficulty dealing with the different value systems of others Physicians may be insecure about limitations of their own competency or skill Physicians may be unaware of prognosis or treatment options and misinform the family or patient's proxy Physicians may not understand ethical, legal, or hospital policies regarding end-of-life care A lack of training in symptom management may lead to inappropriate care Physicians may be ill-trained in interpersonal communication regarding end-of-life care decisions, leading to misunderstandings, confusion, and frustrations

The culture of the hospital may lead to "high-tech" interventions and avoidance of time-consuming conferences with family member

To improve decision making for critically ill patients: First, given the high levels of conflict and the variability in perception of conflict among different staff members, clinicians should strive to recognize conflict so that it can be dealt with constructively. Second, many of the disagreements we identified were not caused directly by different opinions about limiting treatment. Physicians facing a conflict-filled situation should try to determine whether the conflict is actually rooted in a difference of opinion about life-sustaining treatment, or whether it is caused by miscommunication, personality conflict, or unaddressed emotional or social issues. Efforts can then be directed at resolving the particular issue at hand. Third, health care providers should try to identify potentially conflict-ridden situations to prevent discord. Keeping families informed about the patient's response to therapy and what treatment options remain throughout a patient's illness may reduce the likelihood that families will be “blind-sided” by a request to limit treatment. “Preventive ethics” may help avert unproductive conflict and needlessly difficult decisions

Related Documents

Determination Of Death In Children

December 2019 23

Mortality Of Children In Nepal

June 2020 23

Babaji's-(book1) Death Of Death

May 2020 18

Determination Of Protein Content

June 2020 9